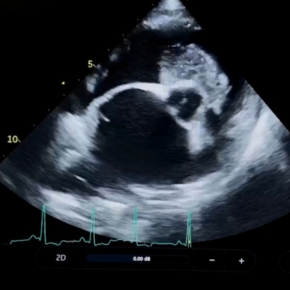

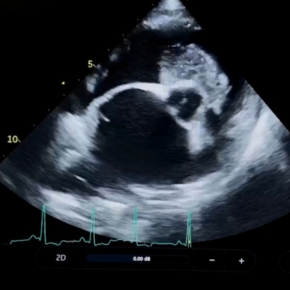

How pimobendan can change echocardiographic findings

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

To round up a month of medical mind-bending in cardiology, we take a closer look at endocrinopathies in dogs with cardiac disease. Hormones have a lot to answer for, but hopefully by end of this article you will know more about what you may be up against in that patient that just didn’t seem to read the rule book on responding to cardiac treatment.

Discover our Comprehensive webinar series on ECG for Nurses

Contact us for help with a case

Just as we discussed with feline hyperthyroidism, concurrent endocrine and cardiac diseases in dogs can mask, mimic, or worsen each other – leading to delays in diagnosis and more complex case management down the line. It is easy to fall into a single diagnosis trap in the early stages, when clinical signs can overlap.

Here’s a breakdown of the major canine endocrinopathies and how they tie into heart disease:

Usually affecting middle-aged dogs, hypothyroidism has a slow onset and vague signs: weight gain, coat changes, recurrent infections. But others – lethargy, panting, exercise intolerance, weakness, bradycardia – could easily be mistaken for cardiac disease, or the two may both be present. Although a causal link has not been identified, hypothyroidism and cardiac disease are common co-morbidities, particularly in middle aged and older large breed dogs.

Hypothyroidism has direct effects on cardiac muscle through decreased ATPase, calcium channel activity, b-adrenergic receptor number and reduced myocardial epinephrine. This causes decreased wall thickness, reduced systolic function and impaired relaxation, which can lead to progressive echocardiographic changes which look extremely similar to early changes in dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). ECG findings include sinus bradycardia, first and second degree AV block, reduced amplitude of P and R waves and T wave inversion.

In dogs with pre-existing heart disease (e.g. DCM, myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)), hypothyroidism can:

Non-thyroidal illness including CHF, can suppress T4 (“sick euthyroid” syndrome”) – so interpret this in line with TSH (which is elevated in genuine cases of hypothyroidism) or Free T4, and recheck following CHF stabilisation.

Thyroid supplementation in patients with existing cardiomyopathy can increase myocardial oxygen demand and may cause decompensation of CHF. Aim to initiate supplementation at a lower dose (25-50% of the usual starting dose) and increase it incrementally, providing the patient remains stable.

Common in dogs over 6 years old, Cushing’s presents with polyuria, polyphagia, skin/coat changes, and truncal obesity. Shared signs with cardiac disease include lethargy, panting, and abdominal distension.

Typically seen in older female dogs, diabetes can have subtle cardiac implications. After a year, some patients have been shown to develop diastolic dysfunction and left ventricular wall thickening.

Cardiac signs in diabetic ketoacidosis include lethargy, tachypnoea and abdominal distension. Marked electrolyte derangement and systemic hypotension has profound effects, particularly in patients with existing cardiac disease. Fluid resuscitation and electrolyte rebalancing is essential, but potentially dangerous in these patients.

Hypoadrenocorticism causes glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid deficiency. Though less common than other endocrinopathies, Addison’s is likely underdiagnosed, with an increased risk in younger females.

Electrolyte changes: (hyponatremia, hyperkalemia) lead to signs that mimic heart disease: weakness, collapse, bradycardia and poor pulses. In Addisonian crisis, profound hypotension and bradycardia may present like end-stage heart failure. However, the mismatch of persistent bradycardia in a collapsed, hypovolemic patient is a red flag and should be investigated immediately.

ECG findings: Sinus bradycardia, high grade atrioventricular block, loss of P waves despite a regular rhythm, tall spiked T waves, VPCs, VT, and even VF due to hyperkalemia and hypoxia. For more help on ECGs, our comprehensive webinar series has got you covered!

These endocrine disorders don’t just coexist with cardiac disease – they can alter its course and confound its diagnosis. Being alert to crossover signs and rechecking values post-stabilisation can help avoid missteps in diagnosis and management. If you need help with a case, take a look at our diagnostic services and do get in touch with our team.

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Understand how left atrial size can cause a cough in dogs with mitral valve disease in our article.