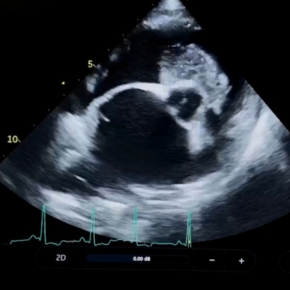

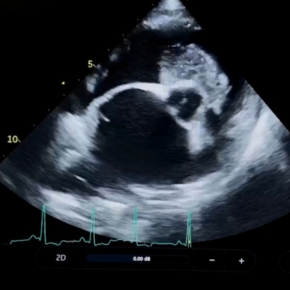

How pimobendan can change echocardiographic findings

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

This article focuses on the presentation of acute left-sided congestive heart failure (CHF) in dogs and cats. Right-sided failure can also present acutely, but patients are generally more stable than those with pulmonary oedema and breathlessness. We are on the end of the phone if you are struggling to stabilise an acute case, or happy to see referrals for further investigations once stabilised.

It’s tempting to assume CHF in a dog with a known murmur and a pronounced cough, but concurrent or unrelated disease is common – and lung crackles alone aren’t diagnostic. Equally not all tachypnoeic cats have cardiac disease.

The key signs include:

Understanding the trigger helps direct therapy, improve outcome and manage owner expectations.

Common causes include:

Your initial aim here is to treat the congestion (by clearing pulmonary oedema) and support cardiac output. Be sure to bear in mind the type of disease process occurring – dogs with volume overload (such as degenerative mitral valve disease, dilated cardiomyopathy) are VERY different to cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (which is a disease of predominantly diastolic dysfunction).

Before diving in and reaching for the frusemide, take a step back and double check the following:

These patients can be tricky to manage, particularly if you’ve taken over a case part-way through. It is always useful to go back to basics if patients aren’t responding as you may expect. And if you aren’t sure, we would be happy to help with case advice or referral.

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Understand how left atrial size can cause a cough in dogs with mitral valve disease in our article.