How pimobendan can change echocardiographic findings

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

A 20th-century physician, John Hickam, once stated that “Patients can have as many diseases as they damn well please” – a valuable reminder not to be blindsided by the diagnosis or treatment of a single condition.

A case that illustrates this perfectly is one many in general practice will recognise.

Chester, a 10-year-old male neutered Shih Tzu, was referred for cardiac investigation following a history of progressive cough and detection of a loud left apical systolic murmur, raising suspicion of congestive heart failure (CHF). He was receiving pimobendan (0.3 mg/kg BID) and had previously shown partial improvement on frusemide (1.7 mg/kg BID), which had since been discontinued.

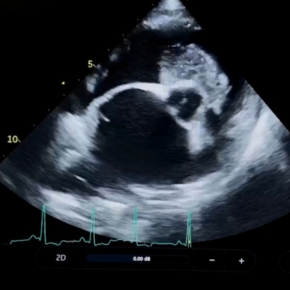

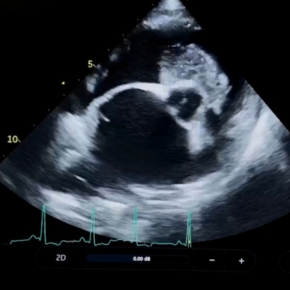

On clinical examination, Chester’s heart rate was 80 bpm with an irregular rhythm and strong femoral pulses, including palpable pulse deficits. A grade IV left apical systolic murmur was present, but pulmonary auscultation and the remainder of the exam were unremarkable.

Diagnostic findings

It’s easy to see how CHF could be considered the cause of Chester’s cough – especially given his partial response to diuretics. Unfortunately, this can lead to a common clinical pitfall: progressive, empirically increased diuretic doses in dogs that never truly respond because CHF was never the underlying problem.

In dogs with left atrial enlargement, mechanical irritation of cough receptors at the tracheal bifurcation can add further confusion. In Chester’s case, the murmur and echo findings could easily have explained away the cough, but further investigation told a different story.

Bronchoscopy, with its ability to visualise airway movement in real time, identified left mainstem bronchial collapse as the primary cause. This changed the management approach completely, allowing for targeted therapy, environmental control, and improved owner understanding of the disease process.

At this stage, Chester did not require diuretics. His management plan focused instead on:

By taking diagnostics beyond thoracic radiography, the true cause of Chester’s signs was identified – sparing him unnecessary medication (and its side effects), reducing owner frustration, and ensuring more effective, welfare-focused care.

Let us know if you’d like help with where to go next with your case, or consider referral for relevant investigations, management and treatment plans tailored to the patient needs and client expectations.

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Understand how left atrial size can cause a cough in dogs with mitral valve disease in our article.