How pimobendan can change echocardiographic findings

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Delayed-release rapamycin halts progression of left ventricular hypertrophy in subclinical feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: results of the RAPACAT trial.

Kaplan J.L, Rivas V.N, Walker A.L, et al. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2023;261(11):1628–1637.

Published 2023 Jul 26. doi:10.2460/javma.23.04.0187

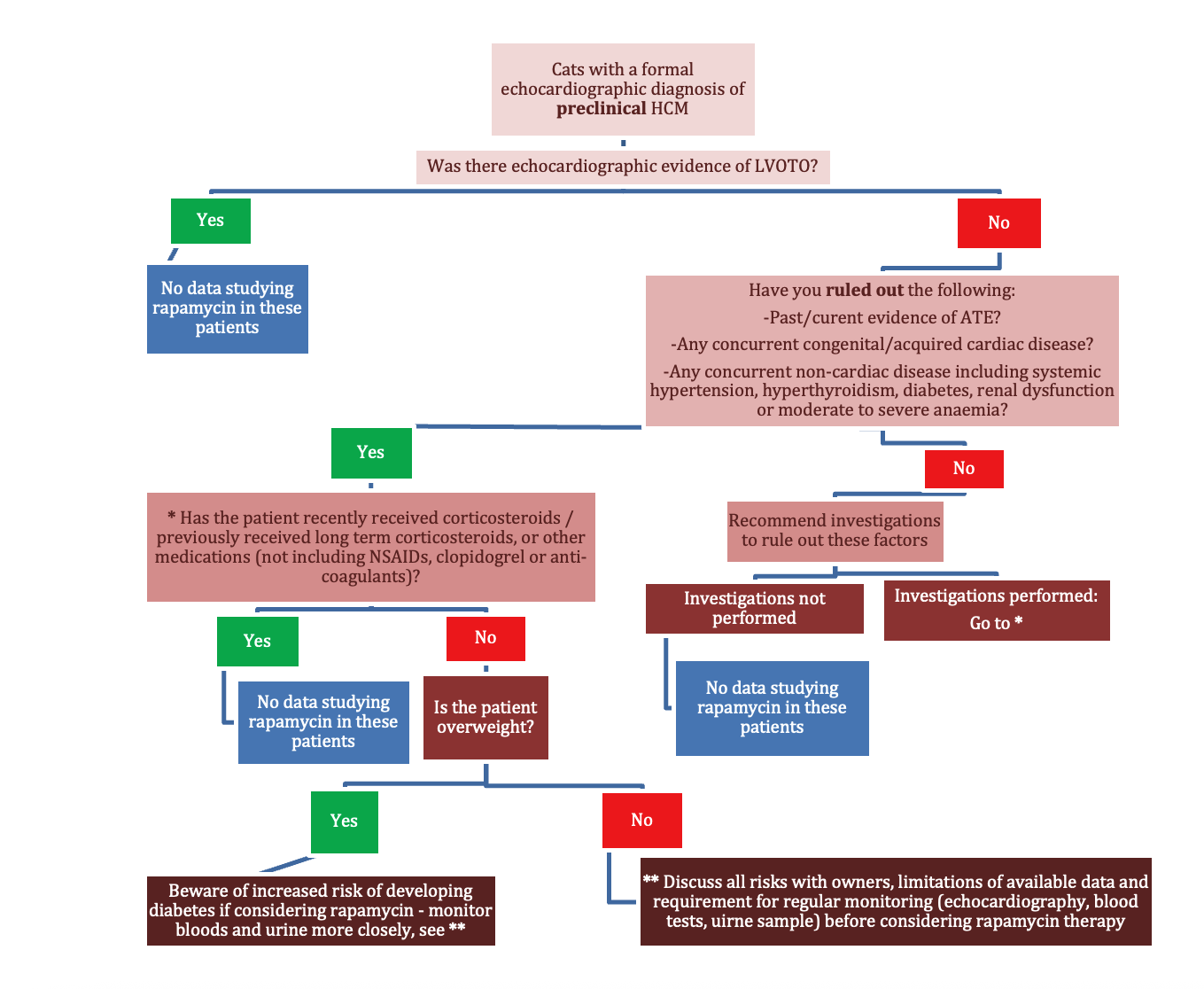

A controversial paper to kick things off – and understandably one of the most commonly asked-about studies at the moment, from vets and owners alike. With feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) affecting so many cats – often with devastating outcomes, the idea of a once-weekly drug that may reverse myocardial hypertrophy has generated huge excitement. Online forums and social media have already crowned rapamycin as a new “wonder drug” for feline HCM. But do we have the full picture? Is it truly as ‘risk free’ as some sources suggest? Let’s take a look.

Rapamycin (Sirolimus) is not new to medicine. It’s a macrolide inhibitor widely used in human renal transplant patients alongside other immunosuppressants, improving survival and reducing organ rejection rates. It binds to ‘targets of rapamycin’ (TOR), inhibiting DNA and protein synthesis, arresting the B-cell cycle, blocking cytokine-induced T-cell proliferation, and reducing immunoglobulin synthesis.

Two multiprotein complexes – mTORC1 and mTORC2, regulate normal cardiovascular health. Chronic haemodynamic stress can activate mTORC1, driving pathological cardiac muscle hypertrophy. This is the key rationale for rapamycin use in HCM.

Intermittent dosing therefore aims to maximise mTORC1 inhibition while limiting unwanted mTORC2 effects. Previous mouse and human studies have shown that mTORC1 inhibition can reverse pathological left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, and canine models of ageing hearts demonstrated improved systolic/diastolic indices with treatment.

This was a randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial across two tertiary centres, enrolling cats with non-obstructive, preclinical HCM.

Inclusion criteria: Cats had to meet all of the following:

43 cats were enrolled; 36 completed the 180-day follow-up.

It has been a long time since a new therapeutic direction has emerged for feline HCM, and this study is an important step in exploring potential future interventions with rapamycin. While the results seem promising, we must avoid giving false hope to owners. Rapamycin is not without risk – it may not be justifiable when applying it to our patients with no clinical signs of HCM and a normal quality of life. The inclusion criteria for cats were highly specific, which means there will be large numbers of our patients that we cannot predict outcomes for. We have no data beyond six months, and no information on how to proceed if one of these asymptomatic cats develops CHF or other complications while receiving the drug.

The study has certainly sparked owner interest – a positive trend in many ways – but the online narrative often oversimplifies the findings. This places the responsibility on vets to remain informed and to guide owners through the nuances of the limited research that we have at present. In suitable individual cases, if an owner is made aware of all of the risks in order to make an informed decision, trialling response to treatment with close monitoring may be worthwhile. But for now, rapamycin is promising, but in our opinion far from ready for widespread clinical use.

Don’t forget, if you need case advice or your client is motivated for referral, we are here to help!

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Understand how left atrial size can cause a cough in dogs with mitral valve disease in our article.