How pimobendan can change echocardiographic findings

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Respiratory disease can be a minefield – multiple causes, overlapping signs, and rarely one simple diagnosis. It’s no wonder these cases feel frustrating. Add in a heart murmur and the thought of anaesthetising for investigations becomes even more daunting.

It’s easy to assume congestive heart failure (CHF) is to blame, but if a patient shows little or no lasting response to furosemide (or even if they do), another culprit may be hiding in plain sight – pulmonary hypertension (PHT).

Importantly, you won’t diagnose PHT from a thoracic radiograph or bronchoscopy. Doppler echocardiography is essential to assess the multiple factors involved. This article aims to clarify what PHT actually is, how to recognise it, and when not to reach for sildenafil. Getting it right can genuinely mean the difference between life and death.

If you suspect PHT in a case but need guidance on diagnosis or management, we’re always happy to help with cardiologist assessment or direct case advice.

PHT almost always develops secondarily to another disease process. When correctly diagnosed, it can be very rewarding to treat, often transforming patient quality of life.

It’s defined as elevated pressure within the pulmonary blood vessels (not the airways). The 2020 ACVIM guidelines classify PHT into six categories, the most common being Class II – secondary to left-sided CHF. We also see many patients with non-cardiac causes, which require a very different approach.

Patients may present with exercise intolerance, episodic weakness or collapse – often before any obvious respiratory signs. When present, signs can include cough, increased effort, or tachypnoea (usually worse after exercise or exertion).

The respiratory pattern can offer clues: these patients often have an expiratory ‘push’, with moderately elevated rates rather than the rapid, shallow breathing typical of pulmonary oedema. (If both left-sided CHF and PHT coexist, the pattern can be harder to distinguish.) Some may also present with ascites.

Why does the pathophysiology matter?

Understanding the underlying cause guides treatment. Don’t reach for sildenafil as a blanket fix – there is usually a reason for raised pulmonary vessel pressure, and addressing that cause is key.

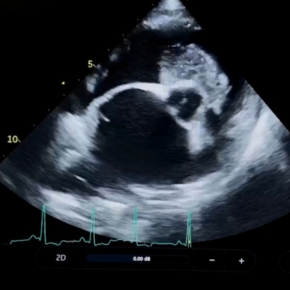

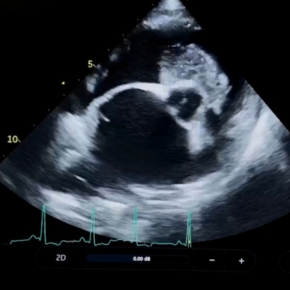

In Class II (secondary to CHF), pulmonary hypertension develops as chronically high pulmonary venous pressure leads to vascular remodelling and vasoconstriction. This increases resistance and pressure within the pulmonary circulation. The right ventricle has to work harder to pump blood out through the pulmonary artery which leads to eventual right-sided enlargement. On echocardiography, you may see right-sided dilation, increased tricuspid regurgitant velocity, pulmonic regurgitation, and right ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Treatment depends entirely on the underlying cause — particularly in Class II cases, where addressing CHF is lifesaving.

Patients in active left-sided CHF need prompt stabilisation and cardiac management. First-line therapy includes appropriate diuresis and pimobendan to support function. Don’t forget to look for triggers of destabilisation (for example, new or worsening tachyarrhythmia).

Once the patient is stabilised, you may see reduced tricuspid regurgitant velocity and improved cardiac function. If PHT persists despite resolving pulmonary oedema, and other causes have been excluded, you can consider cautious sildenafil use at lower doses, ensuring owners understand the potential risks.

Pulmonary vasoconstriction can be ‘protective’, reducing blood flow into pulmonary capillaries. Sildenafil’s vasodilatory effect can ‘open the floodgates’, overwhelming the capillaries and causing acute or worsening pulmonary oedema – patients can deteriorate rapidly.

If congestive heart failure is well controlled but the patient develops collapse or ascites, sildenafil may be introduced cautiously once other causes (such as arrhythmia) have been ruled out.

Repeat echocardiography can help track changes in PHT indices, but don’t rely on echo alone – clinical improvement is often a better indicator of success. Some patients show little measurable echo change despite feeling and functioning far better.

Never underestimate the importance of client communication. Many owners understandably want a ‘quick fix’ without realising the complexity or risks of inappropriate treatment. Explaining early why investigation and accurate diagnosis matter can dramatically improve outcomes and compliance.

And remember – if you’re unsure or the case feels increasingly complex, we’re more than happy to help.

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Understand how left atrial size can cause a cough in dogs with mitral valve disease in our article.