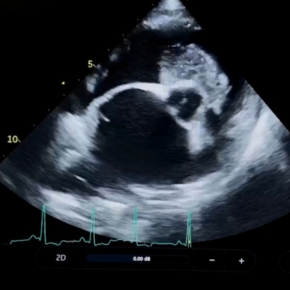

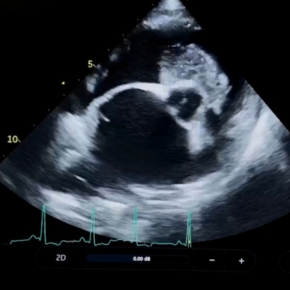

How pimobendan can change echocardiographic findings

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Even for the well-trained eye, early cardiac disease doesn’t always leave obvious clues. Subtle murmurs, fleeting arrhythmias, or even a perfectly normal exam can mask significant pathology.

The best veterinary care is proactive: spotting those early warning signs can extend – and sometimes save – lives. Here’s how to recognise the small clues in your clinical examination of asymptomatic patients that can make a big difference. Remember – if you aren’t sure, we are here to guide you if you need help.

When you’re not listening for a sign of mitral valve disease in a small breed, it’s easy to dismiss a low-grade murmur in a big dog with no clinical signs. But dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) often starts silently – and the preclinical phase is where vets can make a huge impact.

In DCM, early left ventricular enlargement leads to stretching of the mitral valve annulus, creating a subtle systolic leak. The regurgitant jet is usually central, not causing vibration of the atrial wall. Particularly in a deep-chested dog, the sound may be faint or distant on auscultation, making it easy to miss.

Just as ventricular arrhythmias in large-breed dogs with preclinical DCM can appear long before a murmur or echo changes, the same is true for ARVC in Boxers and English Bulldogs.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) can result from structural cardiac changes in small or large breeds – older or more sedentary patients may still appear ‘normal’. AF in large breeds can occur in isolation but can also precede the DCM phenotype in some giant breeds sch as Irish Wolfhounds, and increases the risk of sudden death. Single SVPCs or VPCs may signal underlying structural changes, from acquired disease to neoplasia. Even a rhythm that sounds regular (such as supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) or accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR) may have a rate which is inappropriate for the patient situation. What sounds like sinus arrhythmia may be inappropriate for the patient (not young, fit or athletic breed) and may indicate a change in vagal tone or sinus node dysfunction. Don’t forget to feel for pulse presence and quality during auscultation to note any discrepancies.

Often mislabelled as a gallop ‘rhythm’, a gallop sound is the auscultation of a third heart sound caused by changes in myocardial compliance or intracardiac pressure. Even in the absence of a murmur, a gallop is rarely normal and should prompt further investigation.

Not all cats with cardiac disease have a murmur, arrhythmia, or gallop to give an early warning. While many preclinical cases may still be missed, there are two cohorts’ worth extra vigilance:

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Understand how left atrial size can cause a cough in dogs with mitral valve disease in our article.