It’s not uncommon for arrhythmias to cause a ripple of panic in general practice—especially when they present as emergencies. While some rhythms can lead to sudden death and require urgent action, not all arrhythmias are equally dangerous. This guide aims to help you feel more confident identifying which cases truly need emergency intervention. And don’t forget: if there’s evidence of structural heart disease, stabilising congestive heart failure (CHF) remains a key priority.

Get in touch for case support

Before anything else…

There are three key checks to make with any patient showing an arrhythmia – whether it’s an emergency or you’re assessing how close it might be to becoming one:

1. Listen and feel

Always palpate the pulse while auscultating the heart. A rhythm might sound regular, but pulse deficits may reveal otherwise. Are there missed pulses? How often? This can help gauge how much cardiac output is affected.

2. Prioritise an ECG

Even if you only have a multiparameter monitor, capturing a trace is essential. You don’t need to be an expert in interpreting it – we can support you most effectively with a trace to review. Appearances can be deceptive, and misclassifying an arrhythmia can lead to inappropriate treatment. Ideally, use all three leads to help distinguish true abnormalities from artefact.

3. Check blood pressure

Not all arrhythmias are haemodynamically significant. A normal blood pressure may allow a calmer, more investigative approach—even if further workup is still needed.

Define by Rate: Context Matters

Before you panic at a fast or irregular heart rate, take a step back. Is the rate appropriate for the patient’s behaviour, breed or age? Is it consistent with previous visits? Count over at least 30 seconds, ideally listen for 2 minutes, and document your findings for comparison.

1. Emergency tachyarrhythmias:

Sustained or frequent fast rhythms can cause tachycardia-induced myocardial failure (TIMF), increasing myocardial workload and potentially triggering or worsening congestive heart failure (CHF).

Sinus Tachycardia

- ECG: Regular rhythm, narrow QRS complexes, visible P waves before each QRS (with a consistent PR interval).

- Causes:

- Non-cardiac: Pain, pyrexia, hypovolaemia

- Cardiac: Advanced structural disease, often with CHF due to increased sympathetic tone

- Approach:

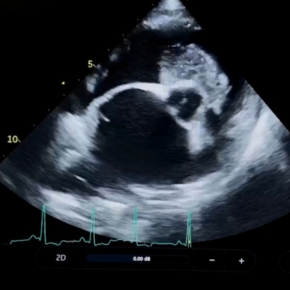

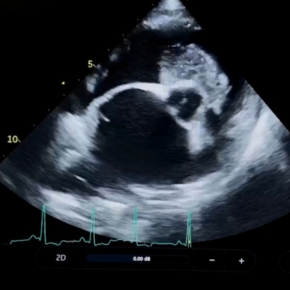

- Address the underlying cause—echocardiography is helpful to assess for structural heart changes.

- In patients with advanced heart disease but no signs of CHF, sinus tachycardia may be an appropriate physiological response to maintain cardiac output. In these cases, you may not need to treat the heart rate directly, provided the structural disease is being managed.

- However, intermittent arrhythmias are common in advanced cardiac disease, and Holter monitoring is particularly useful to assess what’s happening outside the clinic. It can uncover clinically significant or dangerous rhythms that might warrant additional treatment.

Supraventricular Tachycardia (SVT)

- ECG: >4 supraventricular premature complexes (SVPCs) in a row; regular, narrow complexes; typically no visible P waves; rate often 250–350 bpm.

- Clinical Signs: Weak pulses, hypotension or low-normal BP during sustained SVT.

- Causes:

- Cardiac: Atrial enlargement, atrial disease, atrial neoplasia

- Non-cardiac: Systemic inflammation, infection, autonomic imbalance, drug toxicity

- Approach:

- Treat if symptomatic (collapse, weakness) or haemodynamically unstable.

- Try vagal manoeuvres (carotid massage, ocular/nasal planum pressure) to interrupt rhythm.

- Lidocaine may help in specific cases (e.g., focal atrial tachycardia or accessory pathways) but is not first-line.

- Combine Holter monitoring and echocardiography to guide anti-arrhythmic treatment.

Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

- ECG: Irregularly irregular rhythm, no P waves, narrow QRS complexes, often with ‘fibrillation waves’ (F-waves).

- Clinical Signs: Pulse deficits; BP may be low-normal or low, particularly with high rates or structural disease.

- Cause: Atrial enlargement is the most common underlying pathology.

- Approach:

- Treatment is based on mean AF rate (from Holter) and presence of ventricular arrhythmia.

- First-line therapy typically includes diltiazem and digoxin.

- Avoid digoxin if the patient is hypovolaemic, inappetent, nauseous, has gastrointestinal signs, or significant ventricular arrhythmia.

Ventricular Tachycardia (VT)

- ECG: >4 ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) in a row; wide QRS complexes (uniform or polymorphic); no P waves or dissociated P waves; rate usually >200 bpm.

- Clinical Signs: Pulse deficits, hypotension during sustained VT.

- Causes:

- Cardiac: Myocardial disease, inherited arrhythmias, ischemia, inflammation, neoplasia

- Non-cardiac: abdominal disease, drug toxicity, snake bites

- Approach:

- Increasing complexity (couplets, triplets, or runs with fast instantaneous rate) or rapid, sustained or polymorphic VT has an increased risk of deterioration into ventricular fibrillation (VF) or sudden death.

- Treat life-threatening VT with intravenous lidocaine, up to 9 mg/kg over 20 mins.

- Ensure potassium levels are normal – hypokalaemia impairs lidocaine efficacy.

- In cats, use lidocaine cautiously – give slowly and monitor closely for neurologic side effects.

Ventricular Fibrillation (VF)

- ECG: Chaotic, wide, irregular complexes without normal complexes.

- Progression: Typically follows very fast VT.

- Outcome: Rapid blood pressure drop and cardiac arrest.

- Approach: Immediate defibrillation is essential, ideally before CPR is started.

2. Emergency bradyarrhythmias:

Sinus Bradycardia

- ECG: Regular or regularly irregular rhythm, narrow QRS complexes, P wave before every QRS with normal PR interval.

- Clinical Notes:

- Always investigate in patients presenting with shock, significant hypovolaemia, or hypotension.

- Can progress to 1st-degree AV block or atrial standstill in cases of hyperkalaemia, which can be life-threatening.

- Sometimes seen paradoxically in cats with CHF.

- May include pathologic sinus arrest, causing drop in blood pressure and collapse, linked to cardiac (sinus node dysfunction, atrial disease) or non-cardiac causes (endocrine disorders, vagal stimulation, neoplasia, drug toxicity).

- Approach: Suspected sinus node dysfunction (especially in collapsing patients – sick sinus syndrome) warrants Holter monitoring for diagnosis and treatment planning.

Atrioventricular (AV) Block

- ECG: P waves present; PR interval may be prolonged or some P waves not followed by QRS (“blocked”). Escape rhythms can be narrow (junctional, ~60–70 bpm) or wide (ventricular, ~30–40 bpm).

- Causes:

- Cardiac: sinus node dysfunction, AV nodal fibrosis, idiopathic complete heart block

- Non-cardiac: electrolyte disturbances, endocrine disease, respiratory obstruction, drug toxicity Clinical Signs: Pulses typically synchronous and regular Patients may collapse and be hypotensive

- Management Tips:

- Consider atropine response test to see if heart rate increases.

- 2nd degree AV block, Mobitz type II (constant PR interval and block frequency) can progress to 3rd degree (complete) block if frequent.

- 3rd degree (complete) AV block (regular, fast non-conducted P waves persistent with regular, slow escape rhythm):

- Risk of sudden death.

- If idiopathic (no systemic or primary cardiac disease), pacemaker implantation is the most effective treatment.

- Temporary management may include pimobendan or theophylline, but usually only for short-term support.

Atrial Standstill

- ECG: Regular rhythm, absent P waves, narrow (junctional) or wide (ventricular) escape rhythm. Tall T waves may indicate hyperkalaemia.

- Treatment:

- Correction of hyperkalaemia usually resolves the arrhythmia.

- If electrolytes are normal but atrial cardiomyopathy exists, treatment is often unsuccessful, and CHF may develop.

3. The rhythms that can catch you out:

Some emergency rhythms can be tricky and may mimic the arrhythmias we’ve discussed:

- Accelerated Idioventricular Rhythm (AIVR):

- Wide QRS complexes, no visible P waves, often mistaken for ventricular tachycardia (VT).

- Key difference: usually slower (<180 bpm) and patients maintain normal blood pressure.

- Commonly linked to non-cardiac issues like abdominal disease (gastrointestinal, haemorrhage, neoplasia), systemic inflammation or pain.

- Patients with existing structural cardiac disease on anti-arrhythmic drugs (to treat ventricular arrhythmia) may present acutely with CHF decompensation but have slower ventricular arrhythmia.

- Supraventricular Tachycardia (SVT) with Aberrant Conduction:

- May also resemble VT due to wide QRS complexes caused by abnormal conduction.

- More likely to respond to vagal manoeuvres.

- Differentiating between these can be challenging, but that’s why we are here to help!

Key takeaways:

- Always assess pulse quality alongside auscultation to understand the impact of arrhythmias on cardiac output.

- Use ECG (and Holter monitoring when needed) to accurately diagnose arrhythmias before deciding on treatment.

- Identify whether arrhythmias are haemodynamically significant by checking blood pressure and clinical signs—this guides urgency and management.

To update your practice ECG kit, or if you ever want a second opinion or some extra support with tricky cases, just reach out through our website.

And if you’re keen to sharpen your ECG skills, don’t miss our ECG webinar series – there’s always more to learn!

Get in touch