How pimobendan can change echocardiographic findings

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

When presenting acutely, timely diagnosis and treatment of pericardial effusions can make the difference between life and death. Even chronic pericardial effusions will reach a tipping point, although these tend to be less dramatic on presentation. In this article we will cover the clear signs of a pericardial effusion, underlying causes and the most effective approach to maintain a calm head in the emergency scenario.

If at any stage you aren’t sure, we are here if you need advice or swift referral.

The pericardium is a fibrous sac encompassing the heart, normally containing a very small amount of fluid for lubrication. Fluid can build up in the pericardial space due to:

The pressure in the right heart is low (about ¼ of that in the pressure in the left ventricle), so once the pressure in the pericardial space increases above this, the right ventricle will start to collapse, resulting in cardiac tamponade. This impairs filling, reduces output and leads to signs of right-sided failure such as:

Patients with acute effusions often show sudden weakness, breathlessness, or collapse, whereas chronic effusion may cause exercise intolerance, mild lethargy, or progressive ascites. Some may cough, vomit, or retch.

Patients may have some (or all) of the following:

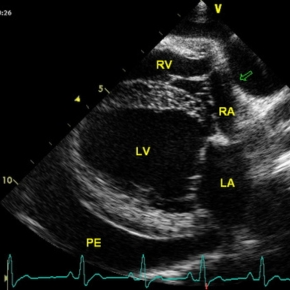

Patients with all of these signs almost certainly have a pericardial effusion unless proven otherwise, but confirmation is always needed with imaging. Standing or sternal thoracic focussed assessment (TFAST) is often enough to visualise the heart and surrounding structures. Some patients also have a pleural effusion, so it is useful to learn to differentiate between the two. Masses can be easier to spot when there is pericardial effusion present, but don’t spend too much time searching for them – it is more important to stabilise your patient. Try to have a subjective view on whether or not there are obvious structural cardiac changes (such as marked chamber enlargement) but remember that systolic function is likely to look terrible in a heart which is being squeezed!

If you’re unsure, save any images or videos and we’ll be happy to review them and advise on next steps. You can also find information on our echo courses, if you’d like to sharpen your scanning skills.

Even idiopathic effusions can recur, so it is important to manage owner expectations. Repeated drainage can cause stiffening of the percardium, increasing the risk of tamponade with smaller volumes. Referral for surgical pericardiectomy is an option to consider after two episodes.

If you’ve diagnosed or suspect pericardial effusion, we’re happy to help. Whether it’s urgent referral, reviewing your imaging, or planning longer-term management, feel free to get in touch.

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Understand how left atrial size can cause a cough in dogs with mitral valve disease in our article.