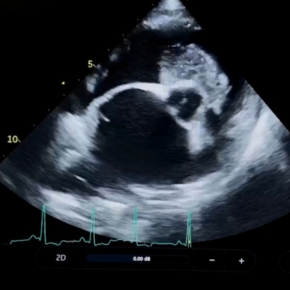

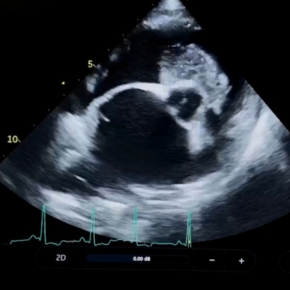

How pimobendan can change echocardiographic findings

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Looking beyond ‘standard medical management’ in cardiac patients reveals a delicate balancing act. We aim to optimise heart function, minimise drug side effects, and manage concurrent non-cardiac disease – often walking a fine line as disease progresses. One of the most complex dynamics is between the heart and kidneys. In advanced cardiac disease, both acute and long-term treatments can compromise renal function, and you can be faced with what feels like an impossible trade-off. Don’t write your patients off yet though! With a strategic approach, we can help support both organs whilst maintain the best quality of life or our patients.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) involves irreversible nephron loss, where treatment aims to slow the self-perpetuating progression. Reduced renal perfusion and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) trigger renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) activation, causing vasoconstriction and fluid retention. While this helps GFR, the resulting volume overload worsens most heart conditions. Diuretic use in congestive heart failure (CHF) can also stimulate RAAS, highlighting the need for careful management of this so-called “cardiorenal syndrome” – where acute or chronic disease of one organ causes acute or chronic disease of the other.

Where situational hypertension has been excluded, attempting to achieve a normotensive patient can be unsuccessful (not to mention extremely frustrating) if the underlying cause has not been treated first. Systemic hypertension (idiopathic or secondary) is both a cause and effect of CKD and can lead to or worsen cardiac issues like increased afterload, left ventricular hypertrophy and valve insufficiency. Conversely, hypotension due to low cardiac output can reduce GFR and organ perfusion. Blood pressure should always be assessed alongside heart and kidney function – it is worthwhile becoming familiar with the ACVIM consensus guidelines for more information. In acute CHF, stabilisation takes priority—persistent hypertension may not resolve until volume overload is addressed. Chronic systemic hypertension can be managed with the following medications:

These medications generally well tolerated as single agents in cardiac disease, although patients should be monitored for evidence of reduced cardiac output and hypotension following treatment initiation. Conversely, hypotension due to low cardiac output can reduce GFR and organ perfusion. Hypotension management requires a cautious approach; fluid therapy may be tempting, but risks exacerbating volume overload (unless in select cases e.g. tamponade) and can be futile when administering diuretics simultaneously. This is particularly challenging in cats with pre-existing HCM, where even small increases in preload (from fluid therapy) can lead to pulmonary oedema as the hypertrophied left ventricle doesn’t stretch to accommodate the added volume. Adjustments to diuresis should be guided by sleeping respiratory rate (SRR) and clinical stability.

Use the lowest dose to manage CHF while limiting renal side effects. Higher doses are often necessary for initial stabilisation but can cause transient renal compromise. When monitoring renal parameters/urine results obtained post-diuresis, be mindful that a degree of dehydration/azotaemia is to be expected and that comparison with baseline (ie pre-diuretic) values is important. Once stable, taper diuretic dose cautiously with close monitoring of clinical signs and SRR. Periodic monitoring of electrolytes is important – particularly where potassium can be supplemented in hypokalaemia. Renal values should not guide diuretics if you are giving the lowest effective dose but may guide additional management.

In proteinuric patients, consider introducing a renal diet with reduced phosphorus, restricted but high-quality protein, controlled sodium, and omega-3 fatty acids. However, maintaining adequate caloric intake is critical – cardiac cachexia is associated with shorter survival time in patients with CHF, and weight loss is a common feature in CKD. If patients don’t tolerate renal formulations, stick to their usual food. Phosphate binders can be used where hyperphosphatemia is present. While there’s no definitive ‘cardiac diet’, a balanced, complete formulation is essential. Ensure water is always freely available.

Whilst it is easy to get tunnel vision in the cardiorenal battle, management of concurrent disease can have huge impacts on your overall therapeutic control. Bear in mind that this may need re-assessment if either disease deteriorates. Endocrinopathies can be masked by cardiac or renal clinical signs but exacerbate existing disease (more on this later in the month!):

As patients accumulate comorbidities, their medication list can become extensive – as well as expensive – reducing owner/patient compliance and raising the risk of adverse effects:

Routine medication reviews are essential as disease evolves. Sometimes you may need to prioritise medications due to side effects, but their impact on patient quality of life should take precedence.

There is no ‘perfect’ solution in managing these cases – compromise is often necessary, usually at the cost of some renal function. Not all cardiac patients will develop CKD, nor vice versa, but early and clear client communication is paramount. Set realistic expectations about disease progression, monitoring, costs, and the importance of recognising clinical signs. Owners who are empowered in this way are more engaged and better prepared to make informed decisions. Long-term patient care is smoother, and patient outcome is usually improved.

Need Support? If you’re managing a complex case and want to discuss it further, we’re here to help.

Avoid misclassification of mitral valve disease in dogs receiving pimobendan

Understand how left atrial size can cause a cough in dogs with mitral valve disease in our article.